What the Lens Does, How That's Described, and Applying Those Descriptions to a Beginner's Lens Purchase

What lens should I get,” is one of the most frequently asked beginner questions. Usually, when asking, the photographer is either so new they don’t own a lens yet, or only has one or two. No matter, we were all beginners once.

The realities of lens choice are closely tied to frequently featured subjects and compositions. Usually lens choice, in terms of broad categories, seems to be only critical at the outset of the photographer’s career. After a while, once that wide angle, normal and telephoto have been purchased, this question usually begins to go away. The reason why is because the photographer will begin to see, in terms of viewing angle, what lens he will prefer to select.

When experienced photographers think about lens choice, viewing angle is an important factor. How much of the world will be included in the frame? This is what drives the lens choice. This is why, for beginners, the kit lens, something with a little wide angle reach (slightly below normal) to short telephoto (slightly narrower than normal) is a good first lens choice. In using the kit lens, the photographer will begin to see in which direction his compositions naturally incline. With the kit zoom, and a little experience, the photographer will naturally notice, “I am using 30mm wide angle all the time, yet it’s not wide enough for me,” etc. Short wide to short telephoto zoom kit lenses are therefore a good first choice.

In the event that a kit zoom is not available, the 50mm lens for 35mm SLR users is an obvious first choice. The angle of view on the 50mm lens in 35mm format is very close to natural vision. Again, with a little experience, the photographer will notice if the framing of the composition will appear wide or narrow enough relative to the first lens used. In this way, many of us have learned to intuit what lens we wish to use based on viewing angle.

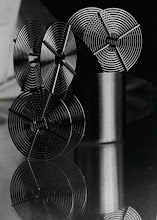

“Macro”, “bokeh”, “magnification”, are all lens-related terms that beginners seem to struggle with. Macro lenses are built internally, with glass lens elements organized so that a very good arrangement of close-ups can be achieved. To do this, the lens designs usually emphasize magnification, with a shallow depth of field. “Bokeh”, a Japanese term for “blur,” is little more than the presence of a blurry area before and after the depth of field.

Any lens can give a “good bokeh.” Placing the blur in a field of view is more of a matter of depth-of-field management in camera operation. If a macro lens is selected, expect the depth of field to be narrow. Meanwhile, any lens can provide “bokeh,” based on choices of focusing distance and aperture; it’s basic depth-of-field management more than it is about lens construction.

“Magnification,” “telephoto” and “zoom” seem to be frequently confused. Many times, I think beginners say that they want telephoto or zoom when what they actually desire is an increase in magnification. While the narrower field of view in telephoto lenses does coincide with some magnification, it pays to know that macro lenses, not telephoto lenses, are designed to optimize magnification. Zoom and telephotos will have some; yet “true” macro has often been regarded as a magnification ratio of 1:1. What that means is one unit before the camera is transposed to the negative as that one unit. A magnification ratio of 1:4, for example, would mean that on the negative, the image is one fourth the size it would appear in reality.

When we want good magnification for close-ups, like detailed photos of plants and insects and very small objects, the photographer will usually strive towards lens choices that lean more toward an increase in magnification than a narrowing of the field of view.

To understand the converse of this, and to place magnification and narrowing into an easier to grasp, think of a sports photographer taking a picture of a football player. The head, shoulders and upper body of a football player on the field are all much larger than the recording surface of the negative. If we were to imagine that we could photograph that football player at a 1:1 magnification from the sidelines, our little 35mm negative or 28mm DSLR sensor would probably get a nice view of the beads of sweat on his face, or maybe his eye will fill the entire frame. We wouldn’t want a 1:1 magnification ratio when photographing an athlete from the sidelines. What we would want, instead, is a narrow field of view, with some modest magnification, to fill the frame with the image.

In understanding the difference between macro and telephoto, it helps to understand which of the two features, magnification and narrow field of view, leads the way. In macro lenses, magnification leads, and a narrowing of the field of view follows as a matter of course. In telephoto lenses, narrowing the field of view leads, and some magnification is designed into the lens as part of making that lens design successful.

The realities of lens choice are closely tied to frequently featured subjects and compositions. Usually lens choice, in terms of broad categories, seems to be only critical at the outset of the photographer’s career. After a while, once that wide angle, normal and telephoto have been purchased, this question usually begins to go away. The reason why is because the photographer will begin to see, in terms of viewing angle, what lens he will prefer to select.

When experienced photographers think about lens choice, viewing angle is an important factor. How much of the world will be included in the frame? This is what drives the lens choice. This is why, for beginners, the kit lens, something with a little wide angle reach (slightly below normal) to short telephoto (slightly narrower than normal) is a good first lens choice. In using the kit lens, the photographer will begin to see in which direction his compositions naturally incline. With the kit zoom, and a little experience, the photographer will naturally notice, “I am using 30mm wide angle all the time, yet it’s not wide enough for me,” etc. Short wide to short telephoto zoom kit lenses are therefore a good first choice.

In the event that a kit zoom is not available, the 50mm lens for 35mm SLR users is an obvious first choice. The angle of view on the 50mm lens in 35mm format is very close to natural vision. Again, with a little experience, the photographer will notice if the framing of the composition will appear wide or narrow enough relative to the first lens used. In this way, many of us have learned to intuit what lens we wish to use based on viewing angle.

“Macro”, “bokeh”, “magnification”, are all lens-related terms that beginners seem to struggle with. Macro lenses are built internally, with glass lens elements organized so that a very good arrangement of close-ups can be achieved. To do this, the lens designs usually emphasize magnification, with a shallow depth of field. “Bokeh”, a Japanese term for “blur,” is little more than the presence of a blurry area before and after the depth of field.

Any lens can give a “good bokeh.” Placing the blur in a field of view is more of a matter of depth-of-field management in camera operation. If a macro lens is selected, expect the depth of field to be narrow. Meanwhile, any lens can provide “bokeh,” based on choices of focusing distance and aperture; it’s basic depth-of-field management more than it is about lens construction.

“Magnification,” “telephoto” and “zoom” seem to be frequently confused. Many times, I think beginners say that they want telephoto or zoom when what they actually desire is an increase in magnification. While the narrower field of view in telephoto lenses does coincide with some magnification, it pays to know that macro lenses, not telephoto lenses, are designed to optimize magnification. Zoom and telephotos will have some; yet “true” macro has often been regarded as a magnification ratio of 1:1. What that means is one unit before the camera is transposed to the negative as that one unit. A magnification ratio of 1:4, for example, would mean that on the negative, the image is one fourth the size it would appear in reality.

When we want good magnification for close-ups, like detailed photos of plants and insects and very small objects, the photographer will usually strive towards lens choices that lean more toward an increase in magnification than a narrowing of the field of view.

To understand the converse of this, and to place magnification and narrowing into an easier to grasp, think of a sports photographer taking a picture of a football player. The head, shoulders and upper body of a football player on the field are all much larger than the recording surface of the negative. If we were to imagine that we could photograph that football player at a 1:1 magnification from the sidelines, our little 35mm negative or 28mm DSLR sensor would probably get a nice view of the beads of sweat on his face, or maybe his eye will fill the entire frame. We wouldn’t want a 1:1 magnification ratio when photographing an athlete from the sidelines. What we would want, instead, is a narrow field of view, with some modest magnification, to fill the frame with the image.

In understanding the difference between macro and telephoto, it helps to understand which of the two features, magnification and narrow field of view, leads the way. In macro lenses, magnification leads, and a narrowing of the field of view follows as a matter of course. In telephoto lenses, narrowing the field of view leads, and some magnification is designed into the lens as part of making that lens design successful.

# # #

No comments:

Post a Comment