No Moving Parts. No Mystery.

No Moving Parts. No Mystery.An updated version of this article in Moving Mirrors.

By John O'Keefe-Odom

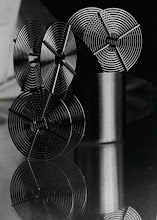

It’s a matter of tension. After the negative is hooked in to the attaching anchor point, either a clip or some protruding prongs, the negative is wrapped around the reel in a way that lets it go from a slightly compressed, curved state to an open an flat one, with the negative inside the tracks of the spiral reel. It takes a little bit of practice at first to get it, but once you do, those reels load very fast and smoothly. Further, there’s a simple way of checking to see if the reel is mis-loaded or the negative is kinked before it goes into solution. The test is a simple tapping of the negative back against the spool walls, it’s easy to tell by touch, and sometimes sound, of the loading reel, that everything has gone okay.

There are a few pitfalls. For example, if the reel is not loaded perpendicular to the central axis of the reel, with every turn, it will get more and more off track. This only makes sense. Imagine a line that is supposed to be horizontal. Instead, it is slightly inclined. As the line is extended more and more, its deviation from horizontal should become more and more obvious. The same type of thing happens with negatives that are anchored or clipped too far out of square with the reel axis. The good news is, usually by one or two turns, the photographer realizes what he has done, and can simply unspool, back up and correct it. Another is that a simple touch-check after anchoring can confirm that the anchor has been set right. Simply take your finger and point it into and along the central axis of the developing reel. You should be able to feel the slight protrusion of the anchored negative. By sliding your finger up and down the axis of the reel, you should be able to confirm, by touch, that a uniform amount of negative projects beyond the axis. Also, you can sometimes tell that you have not fed too much of the negative beyond the center axis.

Sometimes, either at the beginning or the end of the reel, the negative will have a tendency to touch another frame on an adjacent track. In the case of spiral reels, we see that a protrusion beyond the anchor, too far, can cause the very leading edge of the negative’s thickness to touch against a subsequent frame that is wrapped around the reel later. Or, at the end of the negative, sometimes there is a very short section of tightly curled negative. This tight curl is probably from the the winding of the negative onto the spool at the point of manufacture or some other manufacturing-related process. But, it’s there, some additional curl. If this curl is not cut from the negative, it, too, can touch upon a previous frame in the roll; previous, in this case, because the curl is occurring at the very end, and it has a tendency to point downward, into the spool, because the curl of film will encourage a loading of the reel in a direction that is similar to the curl of the negative relative to its original winding on the spool.

No comments:

Post a Comment